Beyond the Denim: Poplar’s Ian Berry on art and community

Ian Berry: Why he no longer wears denim and how in his art “The constant thing, taking away the portraits, is community.”

Entering the apartment-cum-studio where Ian Berry lives, it is unsurprising that denim can be seen everywhere. It is the chosen medium for his art after all. Ducking to avoid the low beams of the converted warehouse space, inside his studio the floor is littered with denim offcuts.

In some places it is knee-deep. A rack of jeans colour coordinated from light to dark, like an artist’s palate loaded with paint waiting to produce a masterpiece, occupies one wall.

What is surprising, is that he isn’t wearing any. He hasn’t worn denim for a while.

‘Last year I stopped wearing it. Sick of it. I caught my reflection in New York wearing jeans, and it just looked really boring.’

‘Swapped to these black pants and ever since, I just haven’t.’

‘I used to say, like, denim is for everyone and art should be for everyone. But I feel my mentality has changed. Art has become more accessible… Instagram and social media has helped younger artists come in and get noticed.’

Ian Berry is an Artist from Huddersfield but has spent the last eight years living in Poplar. Following a less traditional route into art, he studied advertising at Bucks New Uni in High Wycombe.

Described by the Catto Gallery as ‘one of the UK’s Bone Fida art world stars’ it is easy to see why when viewing his work. It is all produced using denim, layering different shades on top of each other to create pictures based on photographs he has taken.

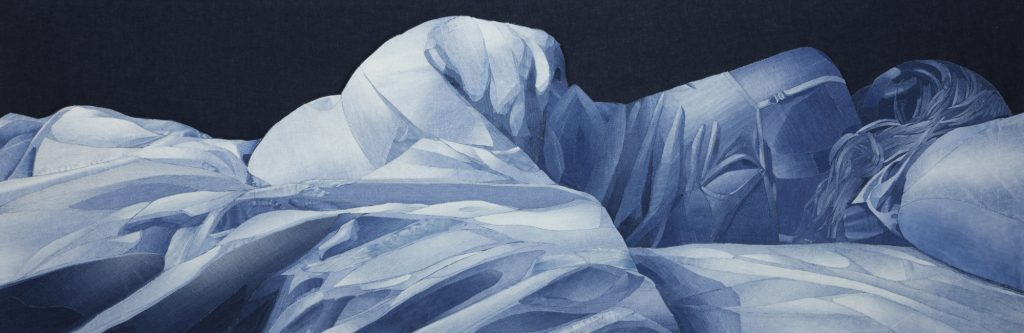

In the space where he lives above his studio, examples of his work can be seen. An elaborate chandelier of dangling flowers, a vase filled with a bouquet, and a large picture of a woman lying in bed facing away from the viewer.

All are made completely from denim.

He’s often asked about different materials, and in light of the lack of denim he is wearing I had to ask too. He replied: ‘I had an idea about doing football shirts. Some people have asked me to do pitches that are different materials.’ However, he has no plans to change anything. ‘The beauty with my denim is it has the shades and the gradients on, whereas other materials don’t have that.’

This can be seen clearly in the picture hanging in his apartment. From a distance, it is easily mistaken for a painting.

Drawing closer you can see the detail. The layers of denim create groves and rises, adding shadows, almost a sculpture. The various indigos combine to create a whole.

It is clear why Ian says it is better to view his work in person, as opposed to in pictures.

Denim is the most obvious unifying factor of his work, but it is not the only one. While he may not get at it directly, ‘The constant thing, taking away the portraits, is community.’

He cites the work he has done relating to record shops and pictures of laundrettes.

‘I think a lot of issues around today are from the lack of community.’

‘I just think about VE day celebrations… There was a community, a support network. People would help each other.’

‘The thing I’ve found is that there’s so many ways to be social now on your phones, but it feels like less. More and more people are becoming isolated.’

‘It is really really lonely to live in a big city.’

Other ideas relating to community he has not yet had time to bring to life. ‘I wanted to do something like local pubs closing down.’ Another idea was ‘workers in Canary Wharf, alone in the offices late at night.’

The latter idea evokes the feelings shown by the picture hanging on his wall. Intensified by the indigos of his chosen medium, it conjures up deep emotions of loneliness.

‘I have one body of work based around that, which was called Behind Closed Doors.’

Ian would create pictures portraying beautiful houses and rooms as you would find in home magazines but with one person in it ‘projecting scenes of loneliness’. The viewer would ask, what are they thinking?

This work was a reflection of a few things including Ian’s own feelings.

‘People had stopped supporting me I’d noticed and just thought “he’s doing really well”, and just assuming. Assuming I’d had money and things.

‘They saw me with famous people, but they didn’t see me the minute before or the minute after. The hard work, which I mean, I’m in the studio alone. I can go a week or two without going out.

‘So yeah, it can be lonely, isolating.’

Recently he curated Art Materialism, almost an antithesis to the loneliness that appears in some of his work. Running as an exhibition at the Cato Gallery in London, it brought together a series of artists like himself who work with unique materials.

‘A part of it was to actually like, build friendships with people and help support each other, because I hate when artists think that there should be rivals. Everything good that’s happened to me as an artist has come from another artist.

‘So I always try and do the same back even if it’s not that same person.

‘It’s a hard enough industry as it is. We all grew up thinking like you can’t be an artist without money. And I grew up with that. That’s why I didn’t do art at uni, later accidentally went back into it. It’s hard work.’

These ideas about community, or the lack of it, stand in contrast to his experience growing up in the North. ‘I grew up where we knew everything about the neighbours. Sometimes too much.’

Unsurprisingly, the community he has built with his neighbours in Poplar is something Ian is very glad of: ‘Here, it’s nice because most of us work from home. So we see each other at different points.’

‘People come and say hi to everyone, and, you know your neighbors.’

Something he likes about the East End is the community that is associated with it: ‘If you said Poplar in East London, to me, in the past, you just think of community’. Though he recognises how that’s changing. Not just here, but everywhere. ‘I don’t know if it’s still there as much anymore. There’s pockets of it.’

Before moving here, he didn’t know a lot about the area, though he does have a personal connection to the East End of London. His grandfather was from Shoreditch and spent much of his life working on the canals in this part of London.

He quickly lists off The Grapes in Limehouse as a pub he likes, and will often take visitors there walking along the canals. More recently he has become a fan of The Old Ship.

The apartment he is still living in is what drew Ian to Poplar. Converted in the 1980s from Spratt’s Petfood Factory, it became one of the first living-working spaces in London. It has since constantly attracted an eclectic mix of artists and creators.

Its unique space designed to be a studio for work and a living area was something he couldn’t find anywhere else. The combination of working and living space is exactly what he wanted for a line of work that is as far away from a 9-5 as possible.

He fell in love with the apartment as soon as he saw it, though he admitted that may have had something to do with the pints he’d had at a pub around the corner before the viewing.

As he shows me the view over the canal from the small balcony, under the quickly darkening winter sky he thinks about how likely it is his grandfather worked on that very same canal.

Moving back inside to take some pictures before the light faded completely, I’m shocked again at the abundance of denim. The more time you spend, the more you realise is made of denim. A cactus hiding in a corner, a side table, a vase. Denim, denim, denim.

To my surprise, as I leave, Ian casually mentioned even the fridge is denim. Though that he bought, instead of made.

If you like this article why not read: Chinese Association of Tower Hamlets: ping pong, calligraphy and tai-chi for a new generation of East End Chinese