The story of Limehouse’s lost Chinatown

Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown, home to a tightly-knit community demonised in popular culture and eventually erased from the cityscape.

“Everybody knew everybody else and we were like one big family,” Connie Hoe remembered. “You shared everything. Shared their worries and their happiness.”

As recounted in the BBC’s ‘Our Greatest Generation’ series, Connie was born to a Chinese father and an English mother in early 1920s Limehouse, where she used to play in the street with other British and British-Chinese children before running inside for teatime at one of their houses.

Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown between the 1880s and the 1960s, before the current Chinatown off Shaftesbury Avenue was established in the 1970s by an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong.

Connie’s memories of London’s first Chinatown as an “urban village” paint a very different picture to the seedy area portrayed in early twentieth century novels.

The pyramid in St Anne’s church marked the entrance to the opium den of Dr Fu Manchu, a criminal mastermind who threatened Western society by plotting world domination in a series of novels by Sax Rohmer.

Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights cemented stereotypes about prostitution, gambling and violence within the Chinese community, and whipped up anxiety about sexual relationships between Chinese men and white women.

Though neither novelist was familiar with the Chinese community, their depictions made Limehouse one of the most notorious areas of London.

Travel agent Thomas Cook even organised tours of the area for daring visitors, despite the rector of Limehouse warning that “those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.”

All that remains is a handful of Chinese street names, such as Ming Street, Pekin Street, and Canton Street — but what was Limehouse’s chinatown really like, and why did it get swept away?

Chinese migration to Limehouse

Chinese sailors discharged from East India Company ships settled in the docklands from as early as the 1780s.

By the late nineteenth century, men from Shanghai had settled around Pennyfields Lane, while a Cantonese community lived on Limehouse Causeway.

Chinese sailors were often paid less and discriminated against by dock hirers, and so began to diversify their incomes by setting up hand laundry services and restaurants.

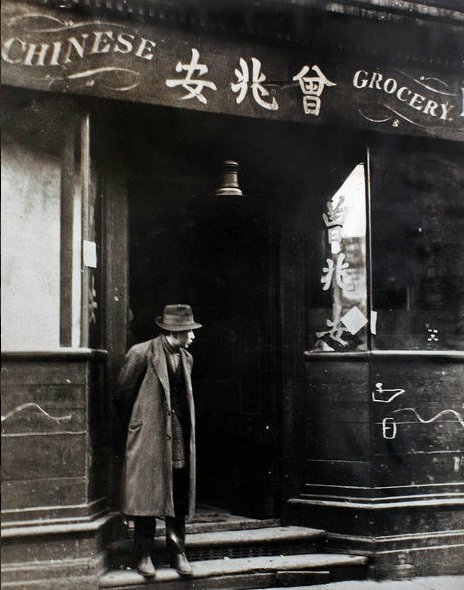

Old photographs show shopfronts emblazoned with Chinese characters with horse-drawn carts idling outside or Chinese men in suits and hats standing proudly in the doorways.

In oral histories collected by Yat Ming Loo, Connie’s husband Leslie doesn’t recall seeing any Chinese women as a child, since male Chinese sailors settled in London alone and married working-class English women.

In the 1920s, newspapers fear-mongered about interracial marriages, crime and gambling, and described chinatown as an East End “colony.”

Ironically, Chinese opium-smoking was also demonised in the press, despite Britain waging war against China in the mid-nineteenth century for suppressing the opium trade to alleviate addiction amongst its people.

The number of Chinese people who settled in Limehouse was also greatly exaggerated, and in reality only totalled around 300.

Both Connie and her husband Leslie remember finding the newspaper reports about their home preposterous in an interview for The Sum of Our Parts: Mixed-heritage Asian Americans.

“[Connie] used to read all these sordid accounts in these two-penny magazines,” Leslie laughed. “We used to think: there must be something going on here, why don’t they let us in on it?”

The real Chinatown

Although the press sought to characterise Limehouse as a monolithic Chinese community in the East End, Connie remembers seeing people of all nationalities in the shops and community spaces in Limehouse.

She doesn’t remember feeling discriminated against by other locals, though Connie does recall having her face measured and IQ tested by a member of the British Eugenics Society who was conducting research in the area.

Some of Connie’s happiest childhood memories were from her time at Chung-Hua Club, where she learned about Chinese culture and language.

In Leslie’s memory, Limehouse was one big playground. He and the other local children would play pranks by knocking on their neighbours’ doors and running away, or they would tie up a paper ball with some string and kick it around like a football.

Leslie’s father worked as a chef in a Chinese restaurant in the West End. At home, he played traditional Chinese instruments and listened to Chinese operas on his gramophone.

Jane Lamb’s father emigrated from Hong Kong and married a Scottish woman in Limehouse. She recalled her father Dr Philip Lamb providing healthcare to the Chinese community free of charge from his practice on West India Dock Road.

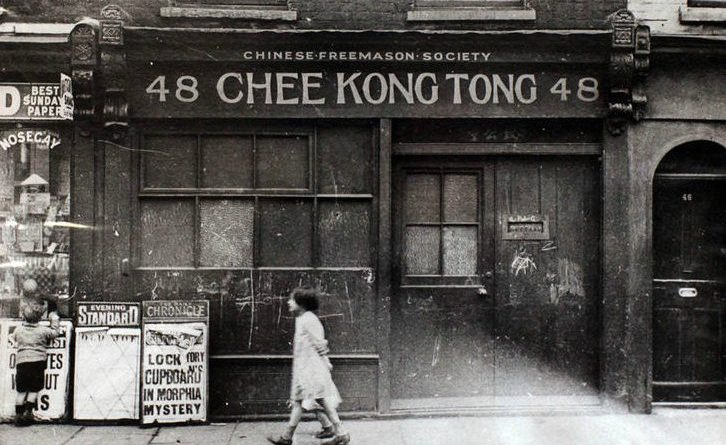

Jane’s father studied at Edinburgh and mingled with highly educated British people, and Leslie recalled Chinese elders who dressed in Western clothes and were members of freemasons societies.

Why did Chinatown disappear?

The caricature of Limehouse’s Chinatown as a den of vice hastened its erasure.

Police raids and deportations fuelled by the alarmist media coverage threatened the Chinese population of Limehouse, and slum clearance schemes to redevelop low-income areas dispersed Chinese residents in the 1930s.

The Defence of the Realm Act imposed at the beginning of the First World War criminalised opium use, gave the authorities increased powers to deport Chinese people and restricted their ability to work on British ships.

Dwindling maritime trade during World War II further stripped Chinese sailors of opportunities for employment, and any remnants of Chinatown were destroyed during the Blitz or erased by postwar development schemes.

But Tower Hamlets still has the third-largest Chinese community in the UK according to the 2011 census, and the Chinese Association of Tower Hamlets was founded in 1983 on Commercial road in Limehouse, near the historic Chinatown.

The Chinese Association provides care for the elderly and language classes, much like Connie’s memories of the Chung-Hua Club where she learned Chinese.

First-hand accounts of Limehouse’s Chinatown are scarce, but the ones that do exist tell of a tightly-knit East End community, one which worked and played together just like any other.

If you enjoyed this, you may like Meet Alan, the 23-year-old at the helm of Poplar’s family-run Vietnamese Supermarket.

Thank you for an intersting read! I was wondering which book amongst the Fu Manchu series mentions the pyramid in St Anne’s?

Very interesting! I came across this researching my Jewish ancestry & found that they were watchmakers, fruit merchants & Dockers clerks and lived in Limehouse causeway in the 1800s.

Thank you for such an interesting article. I’m pretty much hooked in the history of the East end and of course it’s docks. I enjoyed this reading very much

I really love to know more abt Chinatown, when I studied in UK in 80s, my friends told me abt first Chinatown which was not the one in Leister square, however, my friend did not know where was the 1st Chinatown about. What I imagine the earliest days when people fm mainland China migranted in Ldn their lives must be very hard n bitter. Thanks for those forerunners who in fact set up lot of infrastructures n Chinese culture, customs n habits part. Chinese food etc.

I thought the Chung Hua club should gather more Chinese relics, heritage, vintage stuffs… etc so publish books on early Chinese lives in UK !

Fascinating to hear about the first London Chinatown. This was well before my time so I’ve only ever known of the Gerrard Street Chinatown, and just assumed this was the first and only. Next time I’m around the docklands I’ll be sure to take a visit to Limehouse.

I went to school with Hock John Lim , his Father owned the East and West Chinese restuarant in Limehouse. Around 1955 I would stay overnight and help clean tables. It was a pleasure to get to know many of the local Chinese people, Katie, Gordon and Chong. Some of the cooks were cast as extras in the movie The Inn Of Sixth Happiness prison riot scene. I live in the USA now but look back on those days with affection I have tried many times to locate my old friend Hock John Lim but no luck,

I am Hock John’s cousin. We spent our early childhood together in the 1950s in Ilford (my father owned the East & West Chinese Restaurant for many years). Sadly, I have to inform you Hock John passed away in New Zealand in June 2007, where he had lived for many years.

Can you do a guide to Limehouse Chinatown as if we where new Chinese people coming to London for the first time pls.

Excellent article my uncle Stan was adopted 1930s his mother local Poplar girl his dad a Chinese sailor , growing up Poplar early 1960s still quite a few vestiges to be found and those fantastic restaurants,dad and his brother who 1920s lived Upper North Street had some great stories of running through old China town ,part of the Blitzed area was used as a training area for commandos as a urban warfare training area