The Great Dock Strike of 1889: a landmark in trade union history

In the summer of 1889, the dockworkers of East London brought the world’s largest trading port to a standstill. The Great Dock Strike, as it became known, was a landmark in trade union history.

As the long hot days of August melted into September, the docks and warehouses of West India Quay stood eerily quiet. The towering ships that once streamed in and out sat idly at their moorings, the quay, normally a hive sounds and smells, was strangely still.

Across the city at London’s Tower Hill, a cheer went up. The union leader Ben Tillett stepped away from the podium, saluting the thousands of dockworkers who had marched with him through the City of London.

Two weeks earlier, on 14 August 1889, the Great Dock Strike had begun.

For over a month, more than 100,000 dockers and factory workers, many of them residents of the densely populated streets of Poplar, brought the Port of London to a standstill.

They had been pushed to the brink by the precarious and degrading working conditions of London’s docks. The strike was led by ‘casuals’, the lowest rung of dock workers, who were employed on a day-by-day basis to load and unload ships.

The work was unreliable but highly sought after among London’s poor, and each day crowds of desperate men would clamour at the dock gates, fighting amongst themselves to be picked for a few hours’ work.

Those lucky enough to be chosen were scantily rewarded. Dockers received on average 3-7 shillings a week compared to 13 shillings for agricultural workers.

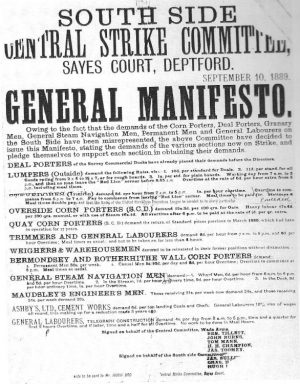

The strikers demanded an increase in pay to the ‘docker’s tanner’ of sixpence an hour – the historic equivalent of the London Living Wage – as well as overtime pay and minimum shift lengths of four hours.

Their action was inspired by a rising wave of working-class unionism. One year earlier in nearby Bow, female workers at the Bryant & May match factory had successfully striked over dangerous working conditions, while a walkout by the National Union of Gas Workers had achieved a pay rise for its members.

As socialist ideas spread around Europe, London’s workers were harnessing the power of collective action.

The spark that lit the fire

On 14 August 1889, a disagreement arose over the payment of a bonus for unloading the cargo ship Lady Armstrong in West India Quay. Ordinarily, a fee was paid to workers for unloading cargo quickly, but dock owners had cut the payment to attract more ships to their quay.

Led by Bristolian union leader Ben Tippett, the dockers of West India Quay walked out. In the days that followed, Tippett and other union leaders galvanised support across the Port of London, and lightermen, rope makers, corn porters, and gas workers joined the strike.

Gradually, walkouts spread to factories and workshops across the East End, and by 27 August a near general strike was in place. Many East End tenants refused to pay rent, and the Port of London ground to a standstill.

The Wade Arms public house on Jeremiah Street in Poplar became the strike’s informal headquarters. The landlord, Margaret Hickey, provided exhausted strike leaders with hearty stews as they drafted their demands and plans of action.

The strikers’ strategy became a touchstone for successful peaceful protest. Along with picketing the docks, the strikers organised peaceful marches through the City of London, and their non-violent protests endeared them to the wider community.

The marches were a thrilling affair. Strikers carried banners emblazoned with slogans, and poles crowned with stinking fish heads and rotten onions representing the poor diet of dock workers. Others rode on floats in fancy dress, presenting scenes that showed the gulf between rich bosses and poor workers.

The Star newspaper reported that “rich men and women waved their handkerchiefs as a token of sympathy with their poor brothers marching below”, and public collections at the demonstrations raised significant funds for the strikers.

The marches frequently ended at Tower Hill, and it was here, in early September, that Ben Tillett addressed the crowd.

Help from Down Under

As September arrived, the greatest threat to the strike’s success was starvation. Without the support of a modern welfare state, strikers had survived on the 25,000 relief tickets handed out by unions each day, which provided strikers and their families with essential meals.

But as time wore on, the unions’ resources were stretched thin, and dock owners knew that hunger could force their employees back to work.

Then, a lifeline arrived. News of the strike had reached Australia and from the beginning of September, £30,000 poured in from trade unions across the country.

As Tillett explained to the crowd, defeat through hunger was no longer an imminent risk. The strikers could double down on their demands.

In early September, the Lord Mayor of London formed the Mansion Committee, a body to mediate between the strikers and dock owners.

With the resources and morale of the strikers bolstered by their new funds, the dock bosses’ hand was weakened, and after much wrangling they agreed to the dockers’ demands.

On 15th September 1889, a victorious rally was held in London’s Hyde Park, with the Australian flag leading the march. And the following morning the dockers went back to work.

The Great Dock Strike was over.

Legacy

The strike of 1889 cemented the London Docklands’ place at the heart of British trade union history. It was a landmark case of collective action by lower-skilled workers, and instigated a huge growth in trade union membership from 750,000 in 1888 to over 2 million in 1899.

Although dockworkers did not gain full job security until 1947, their quality of life improved notably after the Great Dock Strike, with better pay and more regular work.

Years later, Ben Tillett would remark that with the strike of 1889, “The docker had in fact become a man.”

If you enjoyed this, you might like our article about the Poplar Rates Rebellion.

my grand father was William migliori who I understand was a trade union official in the London docks at the time of the great strike. I am seeking further information and would welcome any guidance you might have,

My name is Leonard West and I lived in Providence House from 1939, then we moved down the road to Jamaica House until I was 14 years of age.

My memories are vivid of the years in which I grew up in. Unfortunately some of the years are a distant memorabilia. However I can story many many occasions throughout my growing up years, most of which are locally historic. I would welcome an opportunity to record these in local speak without the unfortunate “Apple and Pears, Daisy Root Chat “.

I there is any one out there interested in these growing up years of the 1940s, I would love to help, putting these on record.