Watching over Limehouse: the secret history of St Anne’s Church

St Anne’s Church guards the secrets of Limehouse from the shadows, but this overlooked Hawksmoor gem is a treasure trove of local history.

Walking down Commercial Road today, it is hard to ignore how different it feels to its sister Commercial Street, the catwalk of Spitalfields shimmering with hotspots. This dual-carriageway was not made for walking but rather built for horse-drawn carts, and later trucks and vans, to cart goods from east to west and back again. While these roads differ in atmosphere, both have been graced with one of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s recognisable churches, with Christchurch Spitalfields tending to overshadow St Anne’s.

As you approach the far eastern end of the road, where it forks into Burdett and East India Dock, a green oasis emerges from the concrete jungle. Crossing the busy road, you leave the unremitting urban landscape to pass into another time.

Georgian terraces line the sides of the St Anne’s square. Some have been beautifully restored – others make peeling paint a part of their charm.

When you finally reach the doorstep of St Anne’s, its white tower draws your gaze skywards.

From naval landmark to horror film set

The church has its origins in a 1711 Act of Parliament. The Act declared that 50 churches would be built across London, targeting underserved areas.

Only 10 new churches ever materialised, one of which was St Anne’s.

Behind the façade of goodwill was an agenda. Lawmakers hoped the Act would help the Church of England regain control over independent religious groups.

St Anne’s was consecrated in 1730 after 16 years of construction. The clock tower remains its crowning glory, doubling as a landmark for sailors on the Thames.

A small stone pyramid in the churchyard may be an abandoned second tower. Or a masonic symbol left by architect Nicholas Hawksmoor, according to some dedicated theorists.

The drama of the place has inspired many. You may recognise St Anne’s from the 2002 horror film 28 Days Later. More recently, it appeared in the BBC’s Call the Midwife, alongside Poplar’s historic housing estates.

Beauty in the shadows

St Anne’s is classic Baroque – an English architect’s take on the Mediterranean. Its dramatic scale, symmetry and contrasting areas of light and shade are all borrowed from Greek and Roman temples.

Hawksmoor spent a good few years in the shadow of his mentor Sir Christopher Wren. But he has now become increasingly popular in his own right.

Ironically for a man of many churches, Hawksmoor has been nicknamed “the devil’s architect” and linked to the occult.

Arguably it is a dark, brooding quality that makes his designs so alluring. St Anne’s is impressive but enigmatic, shrouded in trees and off the tourist track.

A highlight is the east window, a stained glass masterpiece depicting the crucifixion of Christ. It was installed after a fire broke out on Good Friday, 1850. Most of the church’s interior was destroyed and had to be rebuilt.

Last year, Care for St Anne’s (CfSA), the charity responsible for maintenance and restoration, fundraised to repair the window, which was missing multiple panels.

Time, money and other storm clouds

Although Hawksmoor’s fame earned St Anne’s Grade I-listed status, and the surrounding neighbourhood has been a Conservation Area since 1969, the building has not enjoyed the same investment as other churches of its era.

Being located in an overlooked part of Tower Hamlets has made St Anne’s easy to ignore. Its elegant exterior conceals decades of neglect. Inside the church, there is noticeable decay to the ceiling and walls. This is part water damage, part natural wear and tear.

Wooden floorboards from the upper-level peek through where plaster has disintegrated. The paint is peeling, and large chunks of the northwest corner walls are missing. The beautiful ceiling mural is faded, with years of grit obscuring its details.

None of these concerns are new. Care for St Anne’s was set up in 1978 to address the desperate situation. An influx of government money funded repairs during the 1980s, but the cash has dried up.

The building is officially “At Risk”, according to Historic England and the National Lottery Fund has offered £3.5 million towards restoration. But to receive this money, CfSA must match the sum with their fundraising efforts.

Philip Reddaway currently chairs the organisation and says they are about 70 per cent of the way there. If they meet their goal, they will prioritise step-free access alongside repairing damage.

As much as CfSA wants to restore the church to its former glory, there is a plan to expand its role in Limehouse. Reddaway explained:

‘We have a bigger vision for St Anne’s to be used all the time…for education, wellness, culture…It sounds ambitious, but we hope it will become a real community hub.’

Looking back and looking ahead

The multicultural history of Limehouse is an important part of why St Anne’s matters. It has supported one of London’s most deprived communities. It has been a gathering place for residents who have suffered routine discrimination for centuries. Anti-migrant and classist attitudes have marginalised the area’s inhabitants, but the church has been a place of solidarity.

The interior and the churchyard are studded with plaques to residents gone by, commemorating sailors, soldiers and families who have been part of the community.

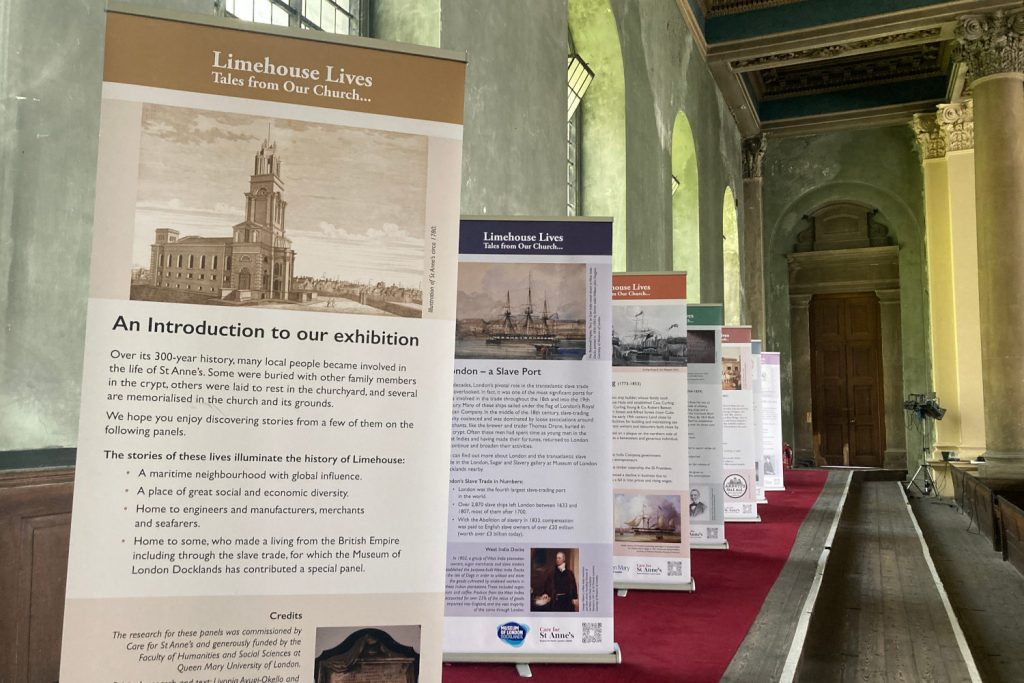

CfSA has opened the church to the public from Thursdays to Sundays, hoping to attract curious passersby. The upper floor houses an ongoing exhibition called ‘Limehouse Lives’ which tells the area’s story through its residents.

The display celebrates but does not sanitise the area’s history. It is refreshingly frank about Limehouse’s role in the slave trade and the exploitation of empire. Going forward, Reddaway hopes to introduce heritage talks and exhibitions of local artwork.

Once enough money has been raised to lift and clean the crypt, the public will be able to tour it and view remnants of the bomb shelter which existed there during WWII.

But Reddaway warned that restoration work will not erase the church’s slightly wild beauty. In some ways, scars of weather and time resemble Venice’s ruined buildings.

He said that sometimes when a church is renovated: “…the finish is so pristine, it somehow loses its magic…[in St Anne’s] the charm, the magic is there.”

More than a building

Reddaway also highlighted the importance of the local community shaping the church’s future. A key challenge is to engage residents who do not identify with Christianity. One of CfSA’s proposals is to transform the churchyard into a community garden tended by locals.

Another goal is to partner with Stitches in Time, located next door at Limehouse Town Hall. The non-profit sewing collective supports women in Tower Hamlets and celebrates their cultural heritage through design. Reddaway hopes to one day exhibit their work inside the church.

Architectural prestige alone should be enough to justify St Anne’s preservation. But ultimately this is more than a building.

Its history is inseparable from the East End’s history as a place of migration and merging. Limehouse has been central to London’s growth into a global city. This church has been the area’s limestone guardian.

With the care it deserves, St Anne’s will guard stories for centuries to come.

If you enjoyed reading this, you may also enjoy our guide to Poplar’s churches.